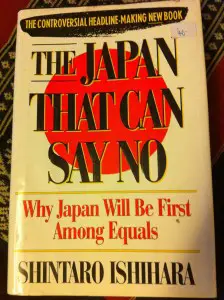

Published in Japanese more than twenty years ago, in 1989, before the collapse of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe, The Japan That Can Say No was officially translated in English and published by Simon & Schuster in 1991. The Japanese version (“No” to Ieru Nihon) was co-authored by Shintaro Ishihara (then Minister of Transport, now Governor of Tokyo) and Akio Morita (co-founder and then president of Sony, deceased in 1999), but the English version included only Shintaro’s part of the book plus a few extra articles that complement his text.

Published in Japanese more than twenty years ago, in 1989, before the collapse of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe, The Japan That Can Say No was officially translated in English and published by Simon & Schuster in 1991. The Japanese version (“No” to Ieru Nihon) was co-authored by Shintaro Ishihara (then Minister of Transport, now Governor of Tokyo) and Akio Morita (co-founder and then president of Sony, deceased in 1999), but the English version included only Shintaro’s part of the book plus a few extra articles that complement his text.

In 2009, Foreign Policy ranked The Japan That Can Say No the fourth worst book on foreign policy in Daniel W. Drezner’s top ten. Now, twenty years after its publication, most of what Shintaro had stated in his book is outdated and Japan no longer has the most active economy. But, at the same time, some of his points about America (especially those regarding military interventions in foreign lands and economic practices) kind of ring a bell in today’s economic crisis.

Shintaro Ishihara is a controversial politician who has succeeded in getting constantly re-elected as Governor of Tokyo since 1999. But, before he became a candidate for the Liberal Democratic Party in 1968, he was an acclaimed writer and actor. His literary debut in 1956 with Season of the Sun (Taiyō no kisetsu) won him both the Akutagawa Prize and the Best New Author of the Year Prize. The same year, he was photographed together with Yukio Mishima, another popular writer and actor of that time.

Reading Shintaro’s The Japan That Can Say No and other articles and interviews with him, I could not help thinking that his preposterous claim that the Rape of Nanking (when tens of thousands of Chinese were raped and murdered by the Imperial Japanese soldiers in China) never really happened is so much like Iranian president Ahmadinejad’s denial of the Holocaust.

The only thing worth quoting from Shintaro’s book is the comparison between fencing and kendo: “In the West, the sport of fencing evolved from warfare, but the foil, epee, and saber never became more than fancy kitchen knives, mere tools for killing people. Japanese swords, however, are works of art. Crafted here by master smiths for more than a millennium, our swords have superb texture, elegance, and balance. Viewing these blades, even non-Japanese sense the mystery of perfection. We redefined a lethal weapon into an aesthetic experience.”

In The Japan That Can Say No, Shintaro Ishihara set out to put the Japan-bashers in their place, only to turn himself in an American-basher.