Most of the Japanese who began reaching Ayutthaya around the turn of the 17th century fell into two groups: merchants and warriors. The two groups were not two rigid entities, since many Japanese immigrants must have belonged to both. This was also the case with Yamada Nagamasa. The merchants sought profit through the booming Siamese trade. The warriors group was formed by soldiers of fortune who could easily find employment in Ayutthaya. Most of them became part of King Song Tham’s bodyguards, or auxiliaries in the Siamese army.

Previously, some of the merchants were Japanese seaborne bandits who, stating the 13th century, had roamed the seas west and south of their native archipelago. By the 16th century, some began to settle in Southeast Asia entreports and to conduct activities not necessarily linked to piracy.

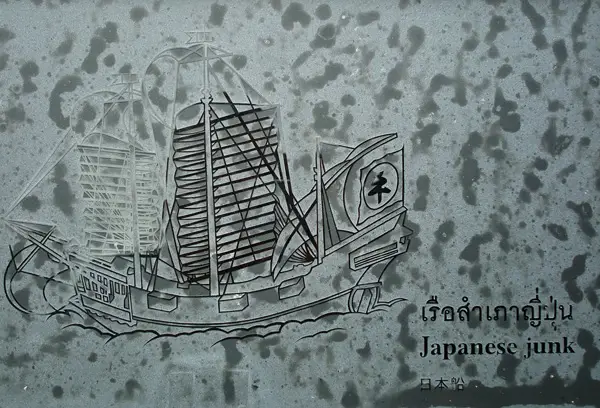

With the beginning of the 17th century, shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu boosted international relations and trade, and eventually a few Japanese merchants began to do business with Ayutthaya on a regular basis through official channels. Some of them were members of wealthy merchant households that decided to reside in Ayutthaya to expand the horizons of their family business. Some others were adventurers who seized the chance and managed to make fortunes. Since their role was crucial for the success of the international trade, these merchants were not only supported by the shoguante, but were also well treated by the Siamese. Thus, many among the Japanese merchants who resided in Ayutthaya were also involved in local military and political affairs, affiliations that facilitated their businesses.

The main products shipped from Ayutthaya to Nagasaki were animal skin: cattle, shark, ray and, especially, deerskin. Other exports included sapanwood, eaglewood and, in minor quantities, rattan, tin, lead, sugar, pepper and coral. In Japan, skins were used to produce gloves, bags, tabi socks, hakama skirts, leather parts for clothes, shoes, and armor. During the 16th century, leather was imported from the Philippines but starting with the 17th century, Siam took over this particular trade.

Payment for the products coming from Siam was made for the most part with Japanese silver. By the time regular trade with Japan began, Siam already had its own silver currency: a coin called baht (the name still used today for the Thai currency).

There was also a third group, that of Japanese workers. Besides those who worked for the licensed shuinsen traders, other Japanese were employed by European merchants, and maybe also by the Siamese, as interpreters and in various positions related to commerce. A Dutch merchant willing to hire Japanese workers in 1613 said they were “clever and their wages low.” Quite a few Japanese laborers worked for the VOC (the Dutch East India Company), where they helped to prepare cargo. The shogunate prohibited the recruiting of Japanese by foreign countries in 1621, though it is unlikely that such a prohibition was extended to the cities of Southeast Asia.

Regarding other occupations, a source mentions a certain Kinoshita Rokuemon, the manager of a small Japanese-style hotel at the mouth of the Menam. In the early 1630s, an actor by the name of Hayami Matasaburo also lived in the Nihonmachi. This proves that the Japanese brought over some of their traditions, including popular entertainment. There are no records indicating that the Japanese living in Ayutthaya engaged in agricultural activities.

Resources: “Samurai of Ayutthaya – The Historical Landscape of

Early 17th Century Japan and Siam: Yamada Nagamasa

and the Way to Ayutthaya” by Cesare Polenghi (p. 26-35)