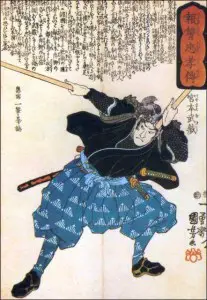

Takezo – Someday he would be known as Japan’s greatest warrior – Musashi. But now he was just an angry young man with dreams of glory, an army straggler from the battle of Sekigahara, on the run from his own villagers, fighting for his future.

Takezo – Someday he would be known as Japan’s greatest warrior – Musashi. But now he was just an angry young man with dreams of glory, an army straggler from the battle of Sekigahara, on the run from his own villagers, fighting for his future.

“At five feet eight or nine, Takezo was tall for people of his time. His body was like a fine steed’s: strong and supple, with long, sinewy limbs. His lips were full and crimson, and his thick black eyebrows fell short of being bushy by virtue of their fine shape. Extending well beyond the outer corners of his eyes, they served to accentuate his manliness. The villagers called him ‘the child of a fat year,’ an expression used only about children whose features were larger than average. Far from an insult, the nickname nonetheless set him apart from the other youngsters, and for this reason caused him considerable embarrassment in his early years.” (p. 32)

“That was Takezo’s nature; he was a creature of extremes. Even when he was a small child, there had been something primitive in his blood, something harking back to the fierce warriors of ancient Japan, something as wild as it was pure. It knew neither the light of civilization nor the tempering of knowledge. Nor did it know moderation. It was a natural trait, and the one that had always prevented his father from liking the boy.” (p. 51)

Matahachi – Takezo’s childhood friend, a strong, affable youth from the Harima mountains who joins his friend’s quest for the honour of battle. When they rose, the sole survivors in a field of dead bodies, their new lives had begun.

“Although it was never used in reference to Matahachi, the same expression [‘the child of a fat year’] could have been applied to him as well. Somewhat shorter and stockier than Takezo, he was barrel-chested and round-faced, giving an impression of joviality if not downright buffoonery. His prominent, slightly protruding eyes were given to shifting when ha talked, and most jokes made at his expense hinged on his resemblance to the frogs that croaked unceasingly through the summer nights.” (p. 32)

Otsu – A foundling, delicate and aloof, she waited faithfully for her betrothed Matahachi, to return from battle to Miyamoto, their home village. But when months passed and he did not come home, she knew it was Takezo she had secretly longed to hold.

“She was a wisp of a girl, with fair complexion and shining black hair. Fine of bone, fragile of limb, she had an ascetic, almost ethereal air. Unlike the robust and ruddy farm girls working in the rice paddies below, Otsu’s movements were delicate. She walked gracefully, with her long neck stretched and head held high. […]

A foundling raised in this mountain temple [Shippoji Temple in Miyamoto], she had acquired a lovely aloofness rarely found in a girl of sixteen. Her isolation from other girls her age and from the workaday world had given her eyes a contemplative, serious cast which tended to put off men used to frivolous females.” (p. 59)

“Otsu was constantly calling out to the parents she’d never known, and they to her, but she had no firsthand knowledge of parental love. The flute was the only thing her parents have left her, the only image of them she’d ever had. When, barely old enough to see the light of day, she’d been left like an abandoned kitten on the porch of the Shippoji, the flute had been tucked in her tiny obi. It was the one and only link that might in the future enable her to seek out people of her own blood. Not only was it the image, it was the voice of the mother and father she’d never seen.” (p. 116)

Osugi – Matahachi’s mother and enemy of Takezo, whom she blames for her son going to war at Sekigahara and not returning back home. He mission in life is to cut Takezo’s head off and she would stop at nothing to see that happening.

“Matahachi’s family, the Hon’iden, were the proud members of a group of rural gentry who belonged to the samurai class but who also worked the land. The real head of the family was his mother, an incorrigibly stubborn woman named Osugi. Though nearly sixty, she led her family and tenants out to the field daily and worked as hard as any of them. At planting time, she hoed the fields and after the harvest trashed the barley by trampling it. When dusk forced her to stop working, she always found something to sling on her bent back and haul back to the house. Often it was a load of mulberry leaves so big that her body, almost doubled over, was barely visible beneath it. In the evening, she could usually be found tending her silkworms.”

Akemi – Daughter of a murdered man, she robbed the bodies of dead soldiers to support Oko, her lascivious mother. She took Takezo and Matahachi, the two teenaged foot soldiers, into their home.

“Though smaller than most of other girls of sixteen, she talked like a grown woman much of the time, and every once in a while made a quick movement that put one on guard. […]

All the same, she was not a girl who’d had anything resembling a proper upbringing. That there was no nobler calling than that of her father [leader of a gang of freebooters] seemed to be something she never questioned. Her mother had persuaded her that it was quite all right to strip corpses, not in order to eat, but in order to live nicely. Many out-and-out thieves would have shrunk form the task.” (p. 38)

Oko – A widow and Akemi’s mother, she tries to seduce Takezo but she is strongly rejected. On finding out that Takezo and Matahachi were intending to return home, she seduces Matahachi and, together with Akemi, run away from Takezo.

“When her husband was alive, Oko had apparently acquired the habit of taking a leisurely, steaming hot bath every evening, putting on her makeup, and then drinking a bit of sake. In short, she spent the same amount of time on her toilette as the highest-paid geisha. It was not the sort of luxury that ordinary people could afford, but she insisted on it and even taught Akemi to follow the same routine, although the girl found it boring and the reasons for it unfathomable. Not only did Oko live well; she was determined to remain young forever.” (p. 41)

Takuan – The Zen priest everyone called crazy. But for Otsu and Takezo, he was a man of indescribable power who held the keys to an extraordinary journey of self-discovery.

“He was born in Tajima Province and started training for the priesthood when he was ten. Then he entered a temple of the Rinzai Zen sect about four years later. After he left, he became a follower of a scholar-priest from the Daitokuji and traveled with him to Kyota and Nara. Later on he studied under Gudo of the Myoshinji, Itto of Sennan and a whole sting of other famous holy men. He’s spent an awful lot of time studying! […]

He was made a resident priest at the Nansoji and was appointed abbot of the Daitokuji by imperial edict. I’ve never learned why from anyone, and he never talks about his past, but for some reason he ran away after only three days. […]

They say famous generals like Hosokawa and noblemen like Karasumaru have tried again and again to persuade him to settle down. They even offered to build him a temple and donate money for its upkeep, but he’s just not interested. He says he prefers to wonder about the countryside like a beggar, with only his lice for friends. I think he’s probably a little crazy.” (pp. 68-69)

Publishing details: Musashi – Book 1: The Way of the Samurai by Eiji Yoshikawa, Corgi Books, Translated from the Japanese by Charles S. Terry, Foreword by Edwin O. Reischauer, 1990, 302 p.

Photo source