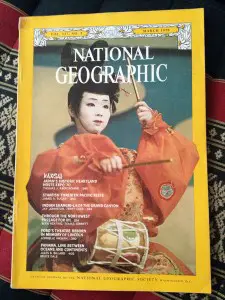

It is amazing the jewels you can find in the book section of Chatuchak Market in Bangkok. Some time ago I bought an old issue of National Geographic which was actually printed almost a decade before my year of birth. The March 1970 issue concentrated on Japan’s Kansai area where, for the first time in Asia, the World Expo ’70 was being organized.

It is amazing the jewels you can find in the book section of Chatuchak Market in Bangkok. Some time ago I bought an old issue of National Geographic which was actually printed almost a decade before my year of birth. The March 1970 issue concentrated on Japan’s Kansai area where, for the first time in Asia, the World Expo ’70 was being organized.

Thomas J. Abercrombie’s heartfelt but analytic article, Kansai – Japan’s Historic Heartland (Vol. 137, No. 3, pp. 295-339), looks at a Japan that, culturally, has remained the same but, economically, has seen great upheavals.

Japan remains “a topsy-turvy land,” as Abercrombie referred to the Land of the Rising Sun in the very first sentence of his article, where, before you enter a house, you take off your shoes (and not your hat), where you scrub yourself outside the bathtub (and not in it), where you mourn the lost ones in white (and not black), where “footnotes” are placed at the top of the page (and not at the bottom as the word itself denotes), where gardens have few flowers, where the wine is heated, where the fish is eaten raw, where cats have no tails, and where women help men with their coats.

Thomas J. Abercrombie (1930-2006) was a senior staff writer and photographer who won some of the most prestigious awards ever given to a photographer. It is thus not surprising that his article about Kansai is littered with poignant photography of a world that seems to be living in the past (portrayed in his photos of the maiko, or geisha-in-training) and in the future (the ’70s were an economic boom for Japan and Abercrombie’s visit to a steel mill in Kobe and a ship yard near Osaka were immortalized in vivid photographs).

The Kansai region, which originally included all the main island of Honshu west of Mount Fuji, encompasses Nara, Osaka, Kobe and, of course, Kyoto. The word “kansai” means “west of the barrier” and, today, the region encompasses only seven prefectures.

2000 years ago, this was the region where the Japanese civilization was born and Kyoto was Japan’s capital for more than a millennium. Today the government operates from Tokyo, but emperors are still crowned in the old capital of Kyoto. The area is filled with historical wonders, such as the Buddhist temple of Horyuji near Nara, which contains the world’s oldest wooden buildings. Nara, also a historical capital city in the 8th century, remains a must-see destination for anyone visiting the Kansai area.

For Kodowaki-san, the President of Kyoto’s English Club, “Japanese food is like the Japanese language. It takes some study and some practice.” He then admits: “Frankly, Japanese is a difficult language – even for Japanese. To pass a college entrance exam, we must know a minimum of 1,850 Kanji, the ancient Chinese characters that form the backbone of the language. We have two different scripts – one for Japanese [hiragana] and another for foreign words [katakana].”

For Kodowaki-san, the President of Kyoto’s English Club, “Japanese food is like the Japanese language. It takes some study and some practice.” He then admits: “Frankly, Japanese is a difficult language – even for Japanese. To pass a college entrance exam, we must know a minimum of 1,850 Kanji, the ancient Chinese characters that form the backbone of the language. We have two different scripts – one for Japanese [hiragana] and another for foreign words [katakana].”

To complicate things even more, “the social position of everyone in Japan is precisely defined, and each must use a style of language proper to his station,” Abercrombie records Kodowaki-san words. “This leads to a profusion of correct forms. One etymologist lists 93 Japanese equivalents of the simple English pronoun ‘I’.”

There’s no article about Japan that doesn’t mention its religion, especially Zen Buddhism which has left a strong influence on the Japanese way of life. An abbot tells Abercrombie that, “In Zen we seek sartori, or enlightenment, by seeing into our own true nature. Briefly, Zen is to grasp ‘what I am’ by uniting body and mind.” Buddhism spread from China to Japan in the 6th century A.D., flowering alongside the native animistic Shinto religion. As such, altars to deities of both faiths stand side by side in many Japanese homes.

And then there’s the tea which, although it was known to the Japanese as early as the 8th century, it became popular only in the 12th century when, explains Abercrombie, “Zen priests began using it as a stimulant to fortify themselves against the rigors of their strict discipline.”

More than four decades have passed since National Geographic featured Japan in its 1970 issue and the changes Japan has seen since then are mostly economic, with people switching jobs more often, rather than remaining employed by the same company for their entire work life. These days, unfortunately, Abercrombie analogy is not longer true: “A man takes a job, as he would a bride, for life.”

One of the most recurring symbols of Japan, the geisha, is maybe the most misunderstood of all things Japanese. Tokuzo Inoue, a famous Kyoto dollmaker, took the trouble to explain: “Most foreigners have the wrong idea about geisha. The word geisha means ‘art person’ – but it is an art few foreigners can understand. Even the new crop of Japanese men no longer appreciates them. Some say geisha are doomed. But I believe that, as long as there is a Japan, they will be with us.”

One of the most recurring symbols of Japan, the geisha, is maybe the most misunderstood of all things Japanese. Tokuzo Inoue, a famous Kyoto dollmaker, took the trouble to explain: “Most foreigners have the wrong idea about geisha. The word geisha means ‘art person’ – but it is an art few foreigners can understand. Even the new crop of Japanese men no longer appreciates them. Some say geisha are doomed. But I believe that, as long as there is a Japan, they will be with us.”

Many travelers schedule their trips to Japan so that they coincide with one of the many Japanese festivals. Abercrombie was lucky enough to witness the decorations people put up for Children’s Day (May 5) when “families deck the sky with paper streamers shaped like carp… The bigger the streamer, the older the son.” The carp symbolizes strength and determination as it is mostly seen swimming upstream.

Thomas J. Abercrombie ends his three-month stay in the Kansai region with a deep feeling of respect for the people, the history and the culture of Japan: “Here is a people, I thought, keeping up with the world in every respect – leading it in some. Yet they know full well that although the present is profitable, the past is priceless. And so, here in Kansai, they go right on living in the best of two worlds.”