The Christian men were probably the only Japanese who brought their Japanese wives with them to Siam. For the rest, it can be assumed that intermarriage between Japanese men and local women (Siamese, Mon or Laotians) was likely, since Ayutthaya was cosmopolitan enough to accept unions between members of different communities.

Apart from Oin, the son of Yamada Nagamasa, historical sources do not mention any child or woman associated with the Nihonmachi. There are also no figures regarding gender-related issues, nor do we have indications about children’s education. Siamese male children received their educations in Buddhist temples, but in the case of the Japanese it is more likely that the sons of traders and warriors were educated in their families. The Christians probably sent their children (both boys and girls) to receive their teaching in the Portuguese enclave, which faced the Nihonmachi on the western side of Menam.

Because children in the Nihonmachi probably grew up in an atmosphere very different from that of Japan proper, we can ask how much these subjects could be considered “Japanese.” The Royal Chronicles state that there were already 500 Japanese in Ayutthaya in 1593. They were for the most part adventurers/mercenaries, and it is unlikely that they brought with them their Japanese wives – if they ever had any. Thus, some of the Japanese residing in Ayutthaya might have paired off with ladies from the region and by the early 1610s (when Nagamasa arrived), there probably would have been a whole generation of young “Japanese-Thai” adults. The males among them were educated in the Japanese martial way. But, it is likely that through constant intermarriage with local women, future generations of Japanese-Thai became absorbed in the mass of the population.

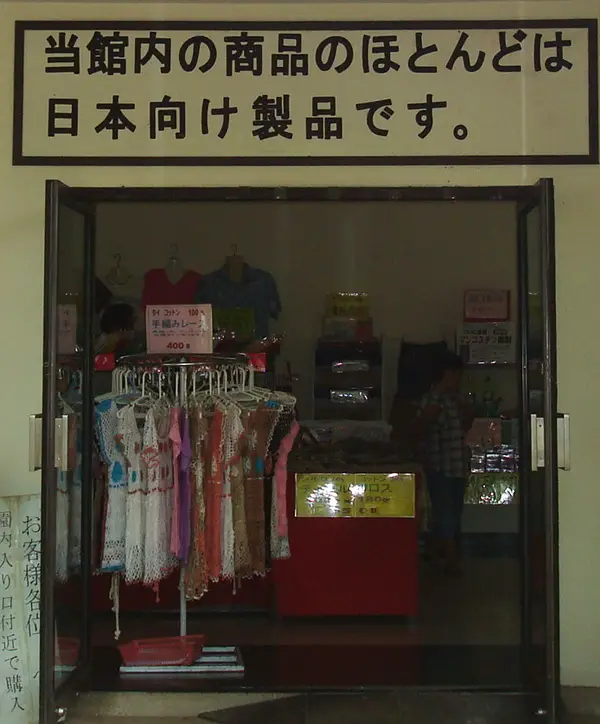

In the 17th century, as is true today, the great majority of the Japanese followed simultaneously their animist tradition (Shinto) and Mahayana Buddhism (a tradition different from the Siamese Theravada form of Buddhism). There are limited by concrete indications that these traditions were transplanted to the Japanese enclave in Ayutthaya, such as, the ema (a votive painting) that Yamada Nagamasa sent to Sumpu and a Japanese-style Buddha head unearthed from the grounds of the Nihonmachi in 1933. (After being brought to Japan, the head was returned to Thailand in 1999, and it is displayed in the small museum in the reconstructed Nihonmachi in Ayutthaya.)

The Japanese Christian community of the Nihonmachi also stands out. During the late sengoku and unification periods (aprox. 1467-1600), Catholicism in Japan had for the most part followed the fortunes of the military leaders who supported it. In particular, the overlord Oda Nobunaga, who abhorred the organized Buddhist militias and was willing to compromise with the Portuguese, tolerated Christianity in order to obtain muskets, gunpowder, and armor for his campaigns.

However, after the death of Nobunaga, the policy towards Christians began to change, and ultimately, under the Tokugawa, they were subjected to a government-sponsored persecution. In 1622, 51 Christians were executed at Nagasaki and, in 1624, 50 more were burned alive in Edo. In total, more than 3.000 Christians were martyred. Those Japanese who fled the country tried to reach the Spanish-occupied Manila region, in the Philippines, but some arrived in Ayutthaya.

We know of the existence of a Japanese church in Phnom Penh in 1618, yet there is no evidence of a similar structure in Ayutthaya. Probably, no Japanese church was ever erected. However, in 1661, across the river from the Nihonmachi, Tommaso Valguarneira, an Italian Jesuit, built a church that was open to the Japanese who still lived in Ayutthaya. In 1662, Lambert, a French father, estimated that there were 1.500 Japanese Christians, a figure confirmed by his colleague, father Deydier, one year later.

Roman Nishi (Nixi) and Petoro (Petro) Kibe, two Japanese Jesuit were spreading the Gospel in Ayutthaya during the second half of the 1620s, when some 400 Japanese Christians dwelled there. They were free to practice their religion, as no opposition came from the Siamese authorities nor from their non-Christian countrymen.

Over generations, both housing and food in the Nihomnachi tended to preserve parts of the Japanese traditional lifestyle in Ayutthaya, who regularly imported goods from their native land. The Japanese residing in Southeast Asia adapted, to a certain extent, to the local architecture and engineering. Japanese furniture and ornaments became fairly common in Siam, and not only among the higher classes. Thus, we may assume that such furniture was also used inside the Nihonmachi dwellings.

Regarding food, the Japanese should have been relatively well off in Auytthaya, considering how their staple diet, based on rice and fish, was easily obtainable and similar to what most Siamese ate. When the Japanese ran out of imported sake, they could drink the local surrogate called arak.

Resources: “Samurai of Ayutthaya – The Historical Landscape of

Early 17th Century Japan and Siam: Yamada Nagamasa

and the Way to Ayutthaya” by Cesare Polenghi (p. 24-29)