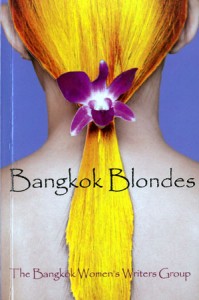

I first heard of Bangkok Blondes sometime in 2007 during a Bangkok Bookcrossers meeting, when the book was introduced to the gathering of book lovers by Anette Pollner, the coordinator of Bangkok Women’s Writers Group (BWWG). What caught my eye from the very beginning was the art work on the cover that depicted the bare back of a seemingly blond woman, with a violet orchid keeping the hair tied together in a tight pony-tail. The book was published by Bangkok Book House in 2007 and was well received on the Thai literary scene.

I first heard of Bangkok Blondes sometime in 2007 during a Bangkok Bookcrossers meeting, when the book was introduced to the gathering of book lovers by Anette Pollner, the coordinator of Bangkok Women’s Writers Group (BWWG). What caught my eye from the very beginning was the art work on the cover that depicted the bare back of a seemingly blond woman, with a violet orchid keeping the hair tied together in a tight pony-tail. The book was published by Bangkok Book House in 2007 and was well received on the Thai literary scene.

It is no secret to anyone that Thailand in general, and Bangkok in particular, is a place mostly favoured by male writers, but Bangkok Blondes comes to make a strong statement which proves this assumption to be incorrect. Fourteen women writers (thirteen Western and one Thai), all members of the BWWG, form a community that needs to be taken into consideration and, I strongly believe, their work needs to be read and critiqued. Among the writers who put together Bangkok Blondes, we have short story writers, poets, essays writers, journalists and, generally, people with a love for the written word.

The book is structured into five parts, titled after the poems by Sarah Sutro that open each section. Although the sections lack a common theme to justify the divisions, it nevertheless, doesn’t obscure the reading experience the book has to offer. However, I personally feel, that the collection would have been more cohesive if the book had been divided according to genres: fiction (short stories), poetry, and non-fiction (essays and articles). This point is something that the writers might want to consider for their second volume.

Following, I will make personal comments of my interpretation of each writer’s text. In the order of their first published piece in the book, I will look at the themes and writing styles of the fourteen women writers and, where I feel relevant, I will quote from their work.

Sarah Sutro, a US poet and painter, writes non-rhyming poetry about the elephants on the streets of Bangkok, the 2004 tsunami, nature and other animals. She also touches upon more abstract topics such as the meaning of life and of the writing experience: “Even the palm at the / end of the mind, / moving by the bank, / in a cluster with / other / is wholeness, / a sentence written / in green – / an anonymous poet, / writing about poetry” (italics from the original).

Martha Scherzer, an American writer, writes short stories about what Bangkok traffic really means and tackles the differences between “a big, fat, hairy, sweaty farang” (the writer herself?) and a Thai behind the wheel. Her other piece in Bangkok Blondes is a heartfelt story about the writer’s experiences as a cancer “survivor” in Bangkok.

Zoe Popham is, along with Chakkaphan ‘Po’ Vutthakanon, the one to “blame” for the excellent cover of the book. She writes short stories about the meaning of wanting something from a culture, but not wanting to be that culture. Other subjects she touches upon are the Thai reverence for any kind of Buddha image, no matter if it’s made of gold or if it’s a plastic kitsch for tourists. She is also baffled by the many grandmothers all Thai families seem to have.

Anna Bennetts, an Australian writer, actress and filmmaker, writes short stories about the huge discrepancies between the Thai’s belief in ghosts and the social life of well-off young Thai women. In a touching story, she also recalls her visit to the notorious Thai prison “Bangkok Hilton” (Klong Prem) where she delivered Christmas lunch to American prisoners.

Anette Pollner is a writer and theatre director who, under the pen name of Ann Cox, has previously published The Company of Frogs, a mystery novel, shortlisted for a UK literary prize in 2007. Her short stories fall in the genre of literary fiction, dealing with unexpected true love found in Bangkok and the writer’s love for trains and the experiences such rides bring along: “Some people go on meditation retreats, and some people get a top notch massage, but for getting in touch with the slowly changing flow of life, I take the train in Thailand,” she concludes.

A trip to a sweet-shop (on foot, this time) turns out to be an encounter with an ambulant stall selling fried insects: “She could distinguish grass hoppers, leaf beetles, skinny spiders and, yes, extremely large cockroaches. They must have led very healthy lives in the jungle.” In The Nomads of Bangkok, the short story that ends the collection, Anette writes about people who took their despair to Bangkok, a place where you can meet a colourful variety of characters.

A trip to a sweet-shop (on foot, this time) turns out to be an encounter with an ambulant stall selling fried insects: “She could distinguish grass hoppers, leaf beetles, skinny spiders and, yes, extremely large cockroaches. They must have led very healthy lives in the jungle.” In The Nomads of Bangkok, the short story that ends the collection, Anette writes about people who took their despair to Bangkok, a place where you can meet a colourful variety of characters.

Chole Trindall, an Australian writer, is the original founder of the BWWG. Her contribution to Bangkok Blondes is a three-part short story entitled Love Bangkok Style, which could have easily been printed in just one block, rather than spread out throughout the book. The first part of the short story deals with the narrator’s new found love and hope in a city too hot for her to be in: “… the ripples of sweat slide down my neck and onto my back I think that I’d rather be anywhere else than here in this hot city full of strange smells and people who chatter away in a language which I don’t understand.” The second part deals with her experiences of marrying a Thai man, while the last part with her decision and preparations to take her husband to Australia.

Jess Tansutat, the only Thai writer among the thirteen female farang writers, is a UK-educated freelance writer currently living in Bangkok. Her short story, Butterfly Game, is the first short story in the collection that really rings a bell. Although in an article for The Star, the coordinator of BWWG refused “to be drawn into a discussion on whether Jess’s story is a cliché,” my feeling is that it is not a cliché, but the hard truth. The story is about the difficulties farang women face in finding a “decent” partner while living in Thailand.

The appealing side of the story comes from the fact that the writer is a Thai woman so, basically, a person on the other side of the barricades (more or less, just like the writer of this review, who is a male farang). Hearing Western women say that “I’m not that picky, but I just find it’s difficult to meet a proper guy here. I want to have someone but I just don’t feel like – well, that I can fall for just any of them,” and having to deal with men who “In their opinion, ladies are like beautiful butterflies – colourful, attractive and sensationally sweet” are just a few of Western women’s frequent complaints.

It’s obvious that the writer is a well-educated, probably fairly rich Thai woman, so the sharp, mocking words addressed in reference to the “more stupid and poorer” Thai women doesn’t come as any surprise. As a foreigner who has been living in Thailand since 2002, I can only disagree with the arguments brought forth. Not all women whom Western men marry in Thailand are poor, stupid girls (with an understatement that they’re from the Issan region). I, myself, am married to a very smart and beautiful Thai woman who earns more money than I do, and is as independent (financially and socially) as any of the other Western women living in Thailand or abroad can be. Does she need my love and protection? Of course she does. But in no less a quantity than I need hers!

Butterfly Game, with a few technical changes, could have been an excellent argumentative essay about foreign women in Thailand. The very few unnecessary details (“I knew they were too good to be real”) only underlines the jealousy felt by a less attractive woman in the presence of a more beautiful counterpart.

Butterfly Game, with a few technical changes, could have been an excellent argumentative essay about foreign women in Thailand. The very few unnecessary details (“I knew they were too good to be real”) only underlines the jealousy felt by a less attractive woman in the presence of a more beautiful counterpart.

Lost in Translation is Jess Tansutat’s other short story in which she writes about the challenges one might have in navigating through all the hard-to-pronounce streets of Bangkok. She bets “that 99% percent of Thais cannot remember its [Bangkok’s] full name,” but I beg to differ. Most of my school students can. Maybe they’re just that 1%!

Janet Geddes has been in Bangkok for almost ten years, so she knows everything about all the great shopping and spa places around the capital. Maybe that is why she writes in her fiction about exactly these things. On a more serious note, Janet also writes about the relationship between Sumalee, a young mia noi (minor wife) and Virote, a rich married man. Sadly enough, even in farang women fiction, money and fancy cars seem to matter most: “‘And here are the keys to that nice new BMW we came in,’ he added. ‘It’s yours.’”

Linn Fitton, a British teacher, writes about dogs, vacuum cleaners, mosquitoes and flies, Songkran time and the Thai bureaucracy. She also describes what riding a motorbike in Bangkok means: “They [the riders] were like hyped up jockeys in the stall at a major horse race, holding back their steeds and awaiting the starting signal.”

Liz Smailes is a freelance journalist and editor from the UK who had the honour of providing the title of the BWWG’s first collection of works. The title story, Bangkok Blondes, deals with the women’s obsession with their hairdressers and, in two other short stories, writes about shoes and colonic irrigations [sic!]. Now, if my male brain makes all the efforts in understanding women’s need for as many beauty accessories as possible (from jewellries to shoes), as well as their need to share these obsessions with the world, it is very hard for me to fathom why on Earth any writer (male or female, for that matter) would choose colonic irrigation as the topic of a short story. I might sound pedantic, but for me such an experience should remain in the privacy of one’s bedroom (or clinic room, to be more exact) rather than in a collection of work that has the potential purpose of empowering women in a post-feminist fashion.

Liz Smailes is a freelance journalist and editor from the UK who had the honour of providing the title of the BWWG’s first collection of works. The title story, Bangkok Blondes, deals with the women’s obsession with their hairdressers and, in two other short stories, writes about shoes and colonic irrigations [sic!]. Now, if my male brain makes all the efforts in understanding women’s need for as many beauty accessories as possible (from jewellries to shoes), as well as their need to share these obsessions with the world, it is very hard for me to fathom why on Earth any writer (male or female, for that matter) would choose colonic irrigation as the topic of a short story. I might sound pedantic, but for me such an experience should remain in the privacy of one’s bedroom (or clinic room, to be more exact) rather than in a collection of work that has the potential purpose of empowering women in a post-feminist fashion.

Ellen Boonstra, an Amsterdam native, writes about the typical characters one can usually find in small offices in Bangkok (but forgets to write about the farangs!), as well as the frustrations that farangs often encounter while making a living in Thailand. She also refers to the language problems she has encountered in the City of Angels and, seemingly as with all women, is obsessed with shopping.

Writing about the sky train, Ellen Boonstra proves to be quite inconsiderate: “Don’t worry about knocking over a few Thais along the way – they’ll live.” Even if it was supposed to be a joke, the Thais would never say such a comment. Proof of this comes from some of Ellen’s BWWG colleagues who even mentioned in Bangkok Blondes the overprotective attitude that Thais have towards their farang acquaintances. Maybe manners and social etiquette are something new that Boonstra should learn from the Thais!

Bronwyn Ure is an Australian “trailing spouse” who writes essay-like compositions about foreigners’ constant sweating problem and, of course, her obsession with market shopping: “So many travelers end up obsessed with bargains and paranoid about being cheated.” She admires the Thais’ ability to stay jai yen (even tempered) as opposed to most farangs who lose control of their feelings for the most unexpected reasons.

Bronwyn Ure is an Australian “trailing spouse” who writes essay-like compositions about foreigners’ constant sweating problem and, of course, her obsession with market shopping: “So many travelers end up obsessed with bargains and paranoid about being cheated.” She admires the Thais’ ability to stay jai yen (even tempered) as opposed to most farangs who lose control of their feelings for the most unexpected reasons.

If the great majority of male farang writers, who live in and write about Thailand, publish books that can be easily labeled as “dick lit,” to some extent, we could say that the women writers of the Bangkok Women’s Writers Guild, with very few exceptions, indulge in writing “chick lit.” However, such recurring topics including ones involving shopping, spas and hair saloons, will not be able to raise the fiction of the BWWG above the level of the go-go bar novel so popular with the farang writers. The least it can do is divide the readership into two separate categories based on gender.

Nevertheless, according to The Nation newspaper, Bangkok Blondes was listed as one of the best books about Asia and one of the four best books about Thailand in 2007. Although the collection is a laudable endeavor, half-way through the book I was looking forward to the more literary fiction of Anette Pollner. I just wish there were more pieces like hers.

In a world where Descartes’s Cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”) mutated into “I’m on Google, therefore I exist,” I was a bit taken aback by the fact that, with very few exceptions, I couldn’t find on the internet any other pieces of writing by almost all of the Bangkok Blondes writers. With the odd Facebook or Twitter account, there were only two or three BWWG members that had work available for the Internet reader to ponder upon. If after reading this review, some might accuse me of bigotry, the lack of information available for each writer to be found is basically close to nill, somewhat calls for deeper understanding on the reviewer’s part.