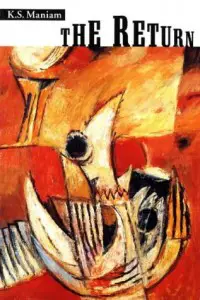

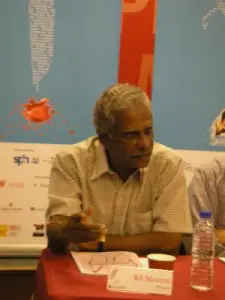

K.S. Maniam is a prolific writer with an impressive academic background. Before turning to full-time writing, he led a life of teaching. His creative work, mostly short stories, has been published in different anthologies of Southeast Asian literature. His published fiction includes collections of short stories, such as Haunting the Tiger: Contemporary Stories from Malaysia, and plays, such as The Cord or The Sandpit. His first novel, The Return, was published in 1981. It was reprinted by Skoob Books Ltd in the Skoob Pacifica Series in 1993.

K.S. Maniam’s autobiographical novel, The Return, presents an Indian boy’s journey of self-discovery while growing up in Malaya. As Dr. C.W. Watson put it in the Introduction to this edition, the novel can be read as a Bildungsroman which deals with the education and the intellectual formation of an unusual young boy who has to go through all the deceptions, sorrows and triumphs life has to offer. Apart from the reconstruction of boyhood, the author also presents the traditions, way of life and difficulties of a community of Indian immigrants.

The sober description of the Indian community’s lifestyle and the faithful representation of a set of extraordinary characters infuse the novel with a textual richness. It is this richness of language that raises the novel above the level of a simple account of success in the face of adversity. In terms of structure, the novel is lacking important elements, evidence of this being the lack of balance between the chapters that form the book. At a point the reader might think that The Return is just a collection of short stories about Maniam’s life, arranged in chronological order, with little connection between them. But the vivid descriptions of the immigrants’ life, the humor in some of the situations and the lyrical characteristics of the text compensate for these imperfections of structure.

The book is littered with Tamil words, a fact that gives the text a special and unique flavor. The few lines of incorrect English used to characterize the language of the immigrants, especially the children’s dialogues, give the reader a glimpse of what the community might sound like. The story is written from the point of view of the narrator. It is a world seen through the eyes of a single person, characterized by the first person singular pronoun “I”.

It is certain that K.S. Maniam had one or maybe more reasons for entitling this book The Return. Anne Brewster suggests in her study, Linguistic Boundaries, that follows the final chapter of the novel, that there are at least three “returns.” The first is the narrator’s return back to Malaysia and his home after two years abroad in England. The second return consists of the author’s return to the experience of childhood through the medium of writing. The final return is the compensation which the author makes in the form of the published novel as a gift to his family and Indian culture.

The author mingles in the narrative themes related to the life and realities of Indian immigrants in a country where, at first, they are looked down upon. The most important of them, as identified by Tang Soo Ping in Renegotiating Identity and Belief in K.S. Maniam’s “The Return”, are: a sense of history, a sense of community, and a sense of character.

The first theme

The first theme, a sense of history, is conveyed almost imperceptibly. Time and place are not mentioned, and the lack of dates (with very few exceptions) makes the reader understand that the author doesn’t want to invoke historical or political events from the history of colonial Malaya. But we are occasionally made aware that the time of the narrative spans over a long period of more than 20 years, from 1940 to 1962. Ravi, the main character, acknowledges the political events that take place in the country, such as the Japanese occupation, the Emergency, and the Independence, but for him they lack social and economic significance.

As we read the novel we understand that as time passes by, modernization is inevitable. The appearance of the cinema, the radio, the bicycle and the car are some of the changes that will eventually influence the social life and prosperity of the characters. Most significant of all, for both Ravi and society in general, is the implementation and extension of colonial education. Some examples are: the addition of new buildings to the school, the movement upwards from one level of schooling to another, the increase in the number of teachers and students, and the social stability that education offers.

The second theme

But all these modernizing factors are also steps that widen the gap between Ravi as part of the poor community of Indian immigrants and Ravi as a member of colonial society. It is this issue that marks the second theme of the novel. The sense of community is described throughout the novel, from its very beginning until the last line of the final chapter. Maniam does not evoke the community in a romantic and sentimental manner, but in a very realistic and sometimes even shocking style. It is a community of immigrants who depend on the system of colonial patronage. At first they are doomed to live in poor conditions on the rubber plantation, from which they draw their livelihood. This community is characterized by anger, violence, conflict and shrewdness.

Ravi is a part of that way of life, but gradually, with the growth of his wisdom through education, he finds a way of getting out of it. Even within the Indian community there are divisions and separation, while class and status are demarcated by territorial and social boundaries. All these are graphically described in the novel, giving the reader a vivid image of how life was in such harsh and unfair conditions. The moment Ravi decides to stay on at school is the first sign he gives to the community that he intends to escape the social status to which he has been associated by birth. As soon as he joins secondary school, he befriends his English-speaking classmates, who are of different ethnic and social backgrounds.

His previous friends, the neighbors’ children, like Gandesh the Indian boy from next door, sense his superiority both at school and at home, and eventually reject him. As soon as Ravi realizes that he can spend his free time reading comics and other books instead of running and playing in the mud, the rejection becomes reciprocal. The detached way adopted by the author in presenting the pettiness and misery of the Indian immigrant community is another proof that Ravi doesn’t consider himself to be a part of it.

The third theme

The third theme, and maybe the most obvious one, is the sense of character described with the same kind of detachment. But there is a big difference between the description of the community and the characters that highly influence Ravi’s life. This difference lies in the closeness the narrator still feels towards such figures as his grandmother and his father. The rendering of their extraordinary lives gives strength to the novel. Apart from these two, there are other individuals who exert a powerful influence upon Ravi: the eccentric schoolteacher Miss Nancy, the superintendent of the hospital compound Mr. Menon and the boy’s stepmother, Karupi.

The Return opens with a description of the arrival of the narrator’s grandmother in Malaysia. She is a strange appearance, carrying her baggage and being accompanied by her three sons. The grandmother is an old woman addressed by the honorific “Periathai”, which means “Big Mother”. She is hardworking and resourceful woman who starts a new life with her family in a strange unwelcome land. At first she works as a tinker, then as a healer, and later on she settles down to farm the land and sell the produce. She draws her vitality from Indian cultural wisdom and experience while the link between everything she does and the Indian tradition accompanies her until death. Periathai never gets to own the house and the land where she has lived on for many years, dying disappointed, speechless and without a farewell.

Although the novel opens with the description of a remarkable woman, the succeeding chapters focus on another figure, the center of authority in Ravi’s life: his father, Kannan. Above all the other characters that shape the life and character of the young boy, his father is by far the most influential. Kannan is a complex character, neurotic but at the same time capable and hardworking. He is highly influenced by Periathai’s vision of life and tradition. Their shared desire to own land and build on it comes from the fact that their roots are still in the farming community Periathai was part of before immigrating to Malaysia. But their wishes and dreams are doomed to failure. Kannan spends the last remaining years of his life in vain, obsessively trying to gain ownership of the land on which he has lived and built his house.

In the years preceding his father’s death, Ravi became detached from Kannan’s and Periathai’s dream of owning land. In just two generations, the dream of the Indian immigrant in Malaysia has disappeared. Ravi, as a representative of the first Malaysian-born generation, sees his community from a different perspective. He does not like the traditional communal lifestyle, and thus decides to pursue more realistic dreams, such as the adoption of the colonial language, English. It is through the medium of this language that he is finally able to move upwards in his social status. It is a language that influences Maniam himself (in fact the main character of the novel) in such a way, that he writes his works in English, and not Tamil, the language of his ancestors.

Ravi will gradually move apart from his family and culture to live in a world influenced by colonial rule. At the moment of his separation he is actually, through education, assimilating another culture. For him, this culture is more rewarding and satisfying that the one in which he has lived. There are two main interrelated reasons that make Ravi decide to estrange himself from the traditions of his family. The first one is the access to a new privileged knowledge that enables him to acquire a different social status. The second is the literature, and the colonial mythology that comes with it, that gives him the capacity to transport himself into a dream world, far away from the poverty and restrictions of his life in the family. Thus, education provides for him not only knowledge, but also a space to retreat into the world of comics, fairy tales, and eventually novels.

Ravi’s schoolteacher, Miss Nancy, is the voice of colonialism. She functions within the hierarchy established by colonialism and imposes her authority through controlling access to English. The passages in the novel that deal with Miss Nancy are characterized by both confession and satire. The humiliation of the young Ravi at the hands of his teacher is avenged by the satire of the narrator. The traditional English fairy tales with which Miss Nancy fills the class are re-told by the narrator as myths of colonial power and the teacher’s sexual frustrations. Although Miss Nancy represents the image of the authoritarian colonial rule, we cannot dismiss her role in shaping Ravi’s interests and intellect which will eventually transform him into a successful, highly educated teacher of English.

Conclusion

“The Return” by K.S. Maniam is a novel that allows the reader the opportunity to be part of a Malaysian experience. It is an experience that brings into light universal existential uncertainties such as adaptation to the ever-changing modern world, the loss of identity, the loss of family and traditional roots, the role of education in life, the opposition between authoritarian and democratic societies, and many more. The novel made me think of my own life and identity. In a way, all of us have to “return” at a point of our lives to some place that is dear to our heart. Either it is our native country, our home, or the place where our parents have grown up, it is a “return” that will always stay in our minds. It is this kind of existential problem that The Return offers us. I recommend it to all readers who are willing to dive free in the fairly new Southeast Asian world of literature.

Bibliography

1. Brewster, Anne, Linguistic Boundaries, in The Return by K.S. Maniam, London: Skoob Pacifica, 1993.

2. Ping, Tang Soo, Renegotiating Identity and Belief in K.S. Maniam’s “The Return”, in Jurnal Bahasa Jendela Alam, 1996.

3. Watson, W.C., Introduction in The Return by K.S. Maniam, London: Skoob Pacifica, 1993.

Photo source