To be able to enjoy Thai literature written in Thai language requires the reader to master the Thai language to a very high standard, well beyond the ability to just being able to read a few road signs or understand the menu at the local soi restaurant. To be able to translate books written by Thai writers into another language requires not only an excellent understanding of how the Thai language works, but a love and affinity for the written word too.

To be able to enjoy Thai literature written in Thai language requires the reader to master the Thai language to a very high standard, well beyond the ability to just being able to read a few road signs or understand the menu at the local soi restaurant. To be able to translate books written by Thai writers into another language requires not only an excellent understanding of how the Thai language works, but a love and affinity for the written word too.

The translation of literary works has always been problematic. There are dozens of books and essays published in academic journals that deal with the benefits of translating a novel, a collection of short stories, a play or a poem word-for-word, thus giving the reader a taste of what the book might sound in its original language. But there are also those scholars who hold absolutely nothing against allowing the translator to have an entirely “free hand” to interpret the text their own way. Peter Montalbano has declared that he strongly believes “a translation from one language to another can never be a one-to-one correspondence of words and phrases, as no two languages have identical sets of these.”

Two examples of this great dichotomy are the French journalist and literary translator Marcel Barang, who has translated into both English and French a great volume of Thai literature at thaifiction.com, and the American musician, writer and literary translator Peter Montalbano, who is currently the translator from Thai to English at Amarin Printing and Publishing in Bangkok.

Following their online debate with regards to the translation of Lap Lae – Kaeng Khoi by Uthis Haemamool, who had won the ‘2009 SEA Write Award’ for the same title, is like watching two heavyweights trying to gain the upper hand in the final rounds of a 12-round boxing match. Their debate on marcelbarang.wordpress.com started straight from the cover of the book concerning Peter Montalbano’s translation of the title itself into The Brotherhood of Kaeng Khoi. His choice of words was contested by Marcel Barang who favours the “word-to-word, sentence-to-sentence, paragraph-to-paragraph approach.”

Regardless of the translator’s philosophy, the ones who immensely benefit from their work are the non-readers of Thai who are given the opportunity to enjoy Thai literature in a language that they can read; the Thai writers whose doors are opened to a much larger readership; and, why not, Thailand itself, which might one day see one of its writers nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

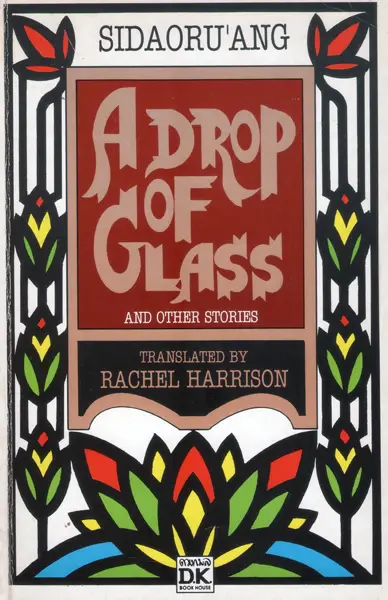

A collection of short stories by a Thai writer which has received several positive reviews within the academic circles of the Western world is A Drop of Glass and Other Stories by Sidaoru’ang, with a translation by Rachel Harrison. Sidaoru’ang is the pen name of Wanna Thaooananon Sawatsri, a Thai fiction writer and representative of the progressive literature movement in Thailand. A Phitsanulok native born in 1943, Sidaoru’ang comes from a peasant background and had personally experienced the hardships of Thai labourers as she herself has previously worked in factories and as a maid in different Thai and foreign households.

Rachel Harrison, the translator of her work, a former resident of Bangkok, currently a lecturer at the University of London, is probably the only foreign academic who has become, over the years, an authority and biographer of Sidaoru’ang’s work and life. Actually, a third of A Drop of Glass and Other Stories (Editions Duang Kamol, 1994) is dedicated to the writer’s life, which she puts in the political, social and literary context of the 1970s. When translating the book, Rachel Harrison, who holds a PhD in Modern Thai Cultural Studies, took a similar approach to that of Peter Montalbano and admitted in the translator’s preface that she gave the book “a distinctive British ring.”

The fourteen short stories that make up A Drop of Glass and Other Stories were written over a long period of time, between 1975 and 1990. Several of these stories describe the plight of Thailand’s working class while Sidaoru’ang’s later work focused on her feminist perspectives, the materialism of Thai society, the destruction of the environment and her alienation with modern urban life.

The title story, “A Drop of Glass,” is a socialist-realist account of the hardships that Thai factory workers have to deal with on a daily basis. Although there is no actual main character, still the story focuses, at least at first, on Anong, a young woman from the countryside whose job was to “pick up each glass, held it to the light and examine it closely. If she found any bubbles or scratches in it, she put it into one box; those which were perfect she put into another.”

Living in very poor conditions, Anong sends most of her salary back home while she could not help wishing she had a proper bed to lie on, with a proper pillow and mattress. She has to suffer at the unscrupulous nature of the factory manager who blames her for not doing her designated job properly.

Mr. Liang, the driver, tells her that she should accept the criticism because “We’re just poor people and we have to go along with what they say. You can take it. Just ignore them. We’ve all got something or other that makes us feel low, you know. I’m just the same. …But then you’re a girl. There’s nothing you can do. The only thing for you to do is not let it bother you. Just get on with your work, that’s the best way.”

In “Father,” Sidaoru’ang pens a sentimental story about the struggle of the Thai lower classes with the harsh reality of their everyday life. Father is a modest man with a big family trying to make an honest living by working at the local railway station in Bang Krathum. He lived, together with his extended family, crammed in a small house where “There was hardly any room left and they all lay so tightly packed together that the net was pulled taut on all sides.”

The many years Father worked, “clad in a kaki uniform,” as the station’s dogsbody eventually take their toll and reduced him “to a virtual invalid, unable to do anything for himself.” Feeling guilty for his failure to give his family a happier life he decides to put an end to all the suffering.

“Go Slay Suriya in the Jungle!” is an essay-like short story about the changes that likay, a form of Thai folk theater, has undergone through the years. The narrator is a writer, “a country girl of peasant stock, and a long standing likay fan,” who recalls how “this newly-opened market down the soi had always put on a free likay show for all the old folk who did their shopping there.” Bemoaning the decay of art in the favour of modern marketing, the likay in the big cities is used as a tool to attract customers: “When new shop-houses and markets are nearing completion, it is customary for the owner to stage a likay performance to encourage people – those lovely people, all those lovely people – to come and buy things in the market.”

The short story ends in a positive note, with the author asking herself what would become of her and her dreams of making it as a writer, hoping that one day her own works will be performed on the stage as likay.

A Drop of Glass and Other Stories by Sidaoru’ang gives very valuable insights into the mind of the Thai working class and their struggle in the context of the 1973 Thai student uprising and the immediate aftermath. Although the book is now out of print, it is still available as a used paperback at Amazon.com and abebooks.com and occasionally at local secondhand bookstores.